January 28, 2016. Lots of folks back home have been asking Matthew and me if we’ve watched Occupied, a Norwegian television drama conceived by the famous Norwegian crime novelist, Jo Nesbø. Our answer is: Nope. Sadly, given that we only get Norwegian Netflix here, we can’t access the English subtitled version of the program. For those of you who haven’t heard of the drama, in short, it’s about what would happen if Russia invaded Norway to take over its oil production facilities. Norwegians have to decide whether they’ll collaborate, or resist.

While the storyline might seem farfetched, in light of recent activities in the Ukraine, the show has definitely touched a sore spot with Russia and given Scandinavians food for thought. I can’t debate the likelihood of such a scenario unfolding, but if it did, I’d put my money on most Norwegians becoming Freedom Fighters. Having just visited Norway’s Resistance Museum, I’d say that these are not a people who can sit idly by while their country is invaded and their government is overthrown. They may be quiet; they may be slow to anger; but they are not passive.

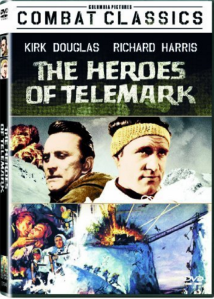

Let me back up a bit. I’m not sure how many of you know Norway’s story during World War II. I certainly wasn’t very familiar it, beyond the standard history lesson categorizing the Scandinavian countries as neutral. But wow, is it an inspiring tale! (And one that has been turned into a made-for-Hollywood movie more than once … but I’ll get to that in a minute.) The tiny little Norges Hjemmefrontmuseum — Norway’s Homefront Museum, better known as the Resistance Museum — presents a whopping amount amount of information on the subject that packs a powerful emotional punch.

To provide you with a bit of a backstory: Norway had just gained its independence from Sweden in 1905 when World War I broke out less than a decade later. Foreign policy wasn’t really a priority for a budding new country working hard to manage internal issues, so Norway elected to remain neutral — a position that was marginally respected and masterfully manipulated by both Britain and Germany throughout the war. Britain threatened to stop supplying Norway with vital coal if the country didn’t cease trade with Germany, while German subs took out Norway’s merchant fleet when their access to the nation’s vast stores of fish and valuable copper, nickel, and pyrite ore was cut off.

The same scenario basically played out at the beginning of World War II. Norway declared neutrality again, hoping to avoid the financial strain of building up a military force. In response, Britain seeded Norway’s waters with mines and planned to invade the country to block German access to Sweden’s iron ores. But Germany jumped the gun and entered Norway before England in an attempt to secure its ice-free harbors and establish a “Germanic Empire.” And that’s why Norway ended up becoming the most heavily fortified country under Nazi rule, with almost 375,000 occupying German soldiers.

The tiny Norwegian Army and Navy didn’t go down without a fight, however. As the German fleet entered Oslo’s waters, torpedoes and gunfire from Oscarsborg Fortress blew up Hitler’s flagship, the Blücher. Its successful sinking in the neck of the fjord delayed the invasion just long enough that the royal family, ministers of office, and the Storting (Parliament) were able to escape. After rejecting Germany’s 13-point ultimatum to surrender, the Norwegian government, King Haakon, and Crown Prince Olav eventually took shelter in Great Britain where they worked with Churchill to plot Norwegian resistance. (FDR offered safe harbor to the Crown Princess and the young future King Harald V and his sisters, who lived in the United States throughout the war.)

Robbed of its chance to control the Norwegian King and government in true puppet fashion, Germany grudgingly placed Vidkun Quisling, the leader of the unpopular Nasjonal Samling (the Norwegian fascist/nationalist party), in power. Quisling was an anti-semite and a wannabe Hitler cohort who saw Germany’s invasion as his “big chance.” Upon hearing of the Nazi fleet’s arrival in Oslo’s fjord, he attempted the world’s first-ever political coup via radio, declaring himself over the air waves to be the new “Prime Minister” of Norway.

German Reich Commander Josef Terboven eventually decided to use Quisling and his puppet party to implement typical Nazi party-line ideals and politics. But the Norwegian people would have none of it. The entire Supreme Court resigned in protest of Nazi legal policies. Teachers chose prison camps in the Arctic Circle over teaching Nazi propaganda in school. Religious leaders suspended church services rather than support the Norwegian Nazi Party. Athletic organizations disbanded rather than tout Nazi rhetoric. Actors, singers, and musicians refused to take the stage in front of Nazi audiences.

In the end, around 50,000 Norwegians were sent to prison camps. One third of the Jewish population in Norway was exterminated. Only about 15,000 Norwegian men volunteered for the Nazi army, while 40,000 joined Milorg, the underground armed resistance movement. Outside Norway, about 28,000 countrymen and women enlisted in Norwegian units within Great Britain’s Allied military, where their movements were directed by King Haakon and Winston Churchill.

One of the most fascinating operations carried out by these exiled troops was the sabotage of the Norwegian heavy-water plant. To explain, heavy water can be used to develop nuclear weapons, and Norsk Hydro, by then under Nazi control, was the first commercial plant to produce heavy water as a byproduct of its fertilizer manufacturing process. The Allies became aware of the situation while working on their own atom bomb and devised a plan to beat the Germans to the finish line.

On October 1, 1942, Allied Forces commenced Operation Grouse (Stage 1 of the plan) which successfully deposited an advance team of four British Special Operations-trained Norwegians behind enemy lines. On November 19th, Operation Freshman (Stage 2) failed when the gliders carrying weapons and backup British paratroopers crashed, killing several of the men and leaving others to be executed by the Germans (41 died in all.)

That’s when things got really tough for the advance team trying to survive on the Hardanger Plateau above the heavy-water plant. The weather was now too rough for British aircraft to make the flight over the North Sea. Snowfall at its heaviest in almost 100 years, temperatures dropping well below normal, and their rations gone, the four Norwegians had to find a way to survive until their compatriots could join them and complete their mission.

They holed up in a hytte (mountain hut), where they spent their days minimizing their movements to conserve energy and telling stories to keep from losing their minds. Reindeer moss became their only source of food, and their bodies went into starvation mode. By the end of two months, the men had each lost more than one third of their body weight. Finally right before Christmas, a herd of reindeer arrived, providing them with protein until Operation Gunnerland (Stage 3) could commence with the arrival of six more Norwegian commandos on February 27, 1943 — nearly five months after the initial team’s arrival.

Despite increased German security, the Norwegian task force managed to sneak undetected into the Norsk Hydro facility. With the help of the plant’s Norwegian caretaker, the team set fuses that destroyed the entire inventory of heavy water (about half a ton) — all without a single loss of life. A British submachine gun had been left behind to direct suspicion away from the locals, but a search was made far and wide for the perpetrators. Six commandos escaped to Sweden on cross-country skis, while four remained behind.

In the 2003 BBC production “The Real Heroes of Telemark,” one of these men tells an amazing story of being chased on skis for hours, while his pursuers dropped from four, to three, and eventually to just one stubborn Nazi who simply refused to give up. The Norwegian describes how this guy dominated on the downhill slopes, but he himself was faster on the uphill portions. Since the Norwegian knew the area intimately, he spent hours trying to ski up, and up, and up, until there was no more “up” available.

Finally, at the top of the mountain range, he stopped, faced his pursuer, and drew his gun. Apparently, the determined but foolish Nazi had neglected to bring a weapon and turned tail to run. The Norwegian shot him and sped back downhill to take refuge in another hytte. It’s a shame the poor guy didn’t try that maneuver earlier and save himself some energy. In the end, the entire series of operations are considered the most successful acts of sabotage completed in WWII.

But there’s a bittersweet ending to the tale. The plant re-started heavy water production shortly thereafter. The Allied air forces began a series of attacks that eventually convinced the Germans to stop production. However, at this point, the Nazis had accumulated another serious stash of heavy water, which they decided to ship to Germany where a nuclear facility was already in production. The single Norwegian commando remaining in the area came out of hiding one night while the cargo sat on a train, awaiting transfer to a ferry that would take the load across Lake Tinn.

Surprisingly, the Germans had stationed all their troops around the train and cargo, but the ferry had no guards. The Norwegian commando managed to affix a series of charges to the ferry’s hull, timed so that they would detonate as the boat reached the deepest part of the lake. The plan came off like clockwork, and the cargo — as well as a number of civilian Norwegian passengers, who could not be warned of the situation without risking the plan’s success — sunk to the bottom of the lake.

While the experts now hotly debate whether Germany was actually capable of building an atom bomb, the fact remains that this group of Norwegians took tremendous risks and endured incredible hardships to make sure it wouldn’t happen. And it seems to me that their actions, plus those of thousands of other men and women who fought for Norway’s freedom during the war, easily put to bed any question posed by Occupied that Norwegians will silently stand by during an invasion by a foreign power. That’s my opinion, anyway, for whatever it’s worth.